MightyUs

Empowering at-risk refugee children to be their own safety superheroes

Overview

SCOPE

8 months (graduate thesis)

CATEGORIES

Research, UX, Strategy, Game Design, Social Impact

RECOGNITION

This project was selected for the Paula Rhodes Award for quality and originality in thesis conception.

MY ROLE

Even though this was a solo project, the development wouldn’t have been the same without the enriching conversations with my advisors, and so many talented people I met along the way.

What is this project all about?

CONTEXT

The ongoing Rohingya crisis has left more than 400,000 children fighting for survival in chaotic refugee camps, where child trafficking is one of the biggest perils they face. Children as young as seven often need to trek through the camps alone. Unaware of the potential dangers, they become easy targets for traffickers.

CHALLENGE

Most existing efforts are geared towards helping victims and few, if any, address prevention — what if we empower children to look out for themselves?

SOLUTION

MightyUs is a workshop that helps refugee children, ages 7 to 10, exercise vigilance and be more confident. Through interactive storytelling, games, and songs they learn to assess risks, practice caution, and be their own safety superheroes. Its learn-through-play approach makes the experience fun and not overwhelming for young children.

Key Features

What are these superpowers?

MightyUs introduces five essential safety skills in the form of superpowers, and takes children on a journey to becoming safety superheroes.

How do children master the superpowers?

To help children better understand these superpowers, they are introduced in a three-step approach illustrated below. *Due to request of privacy, the images below are blurred.

What would the whole workshop experience be like?

What is needed to conduct the workshop?

- Place

- Volunteers

- A 52-page A5-sized guidebook for volunteers to prepare

I imagine MightyUs workshop to be a part of already established learning centers in the refugee camps and can be conducted by trained volunteers, who will be referred to as the “Safety Marshals”.

A safety marshal receives a guidebook, which is the only item needed to conduct the workshop. The guidebook contains all the pertaining information about the workshop (all five superpowers, their related games and songs) and its structure. It also illustrates Safety Marshal’s role and the “dos and don’ts” of working with children based on psychological research.

Goals & Strategies

Process

Research Insights

The Rohingya crisis had just begun when I was brainstorming for a graduate thesis topic, and designing for children has always had a special place in my heart. So I started thinking about how can I contribute to improving the lives of these refugee children. I started with the broad umbrella of safety and well-being, and immediately immersed myself in whatever information I could find about the crisis, primarily in two ways.

- Cold emails + interviews

- Current and past refugees (both adults and children)

- People working at official international agencies (UNHCR, UNICEF, Save the Children, etc) or local NGOs

- Reporters and journalists who have covered refugee crises

- Reading

- Books

- Online articles

- Reports by NGOs working on the crisis

This research helped me uncover many interesting observations about the difficulties that Rohingya children face in the refugee camps. Here are some of the important ones that reveal areas for possible improvement.

OBSERVATIONS

- Identification of families started as late as 40 days after the crisis began, leading to chaos in the beginning. Also, the adversity leads to many children developing toxic stress response, addressing which requires medical and psychological attention. This is difficult in the first few months as not all systems are fully operational yet. The first couple of months could be a great time frame for an intervention.

- Amid all the adversities, the children (and their parents) live under constant threat to their safety. Many children are orphaned or separated from their guardians. Even when they are not, their parents need to go out to earn money and cannot always chaperone the children. On top of this, there is a lack of safe physical environments for the children to play and segregated tents for them to sleep in. Thus, children become targets for trafficking, slavery, physical violence, and sexual abuse. Providing safe environments or supervision can contribute towards keeping the children safe.[1]

- Children also need to go out in the camp to get food or ration. Sometimes, they wander far off and cannot find their way back. Improving night lighting and wayfinding can also contribute towards their safety.

- The Child Friendly Spaces (CFS) established by UN agencies provide great educational and psychological support to children and their parents. There were already 55 static and 42 mobile CFS as of 2nd week of October 2016. There is an opportunity for an intervention to use this already existing infrastructure.[2]

- In my conversations with a psychologist working in the camps, she provided some crucial insights:

- The CFS act as safe havens for parents, who can go find work without having to worry about their children.

- While colors can play wonders, the camp environment lacks visual stimulation.

- Many children start to develop guilt over losing memory of their culture and their lost beloved.

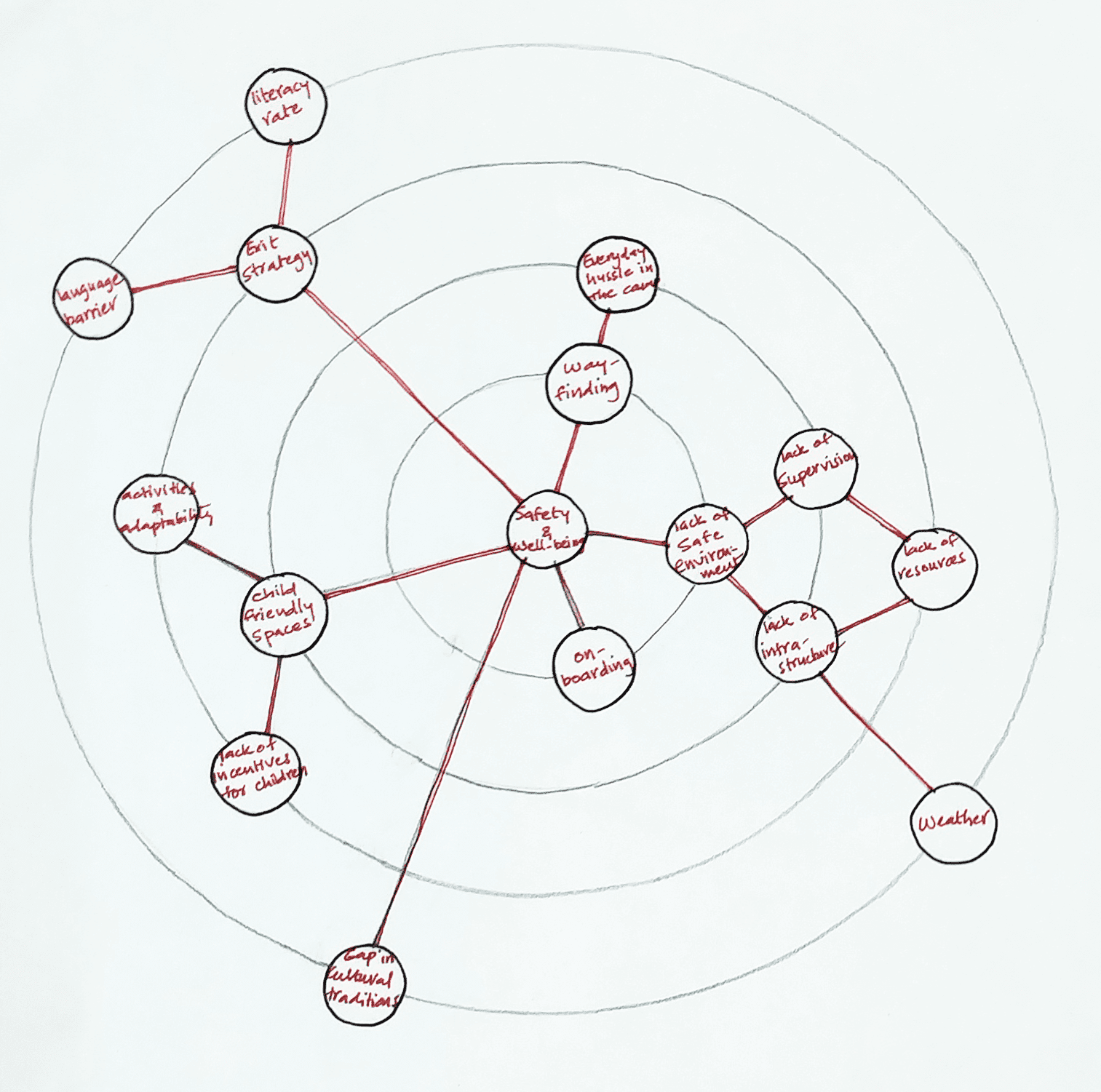

As the next step, I identified the problem areas and classified them in different tiers based on how directly they affect the safety and well-being of refugee children in camps.

I rapidly explored different problem areas, time-boxed each exploration, and evaluated the areas in two key aspects.

- How much potential is there for improvement?

- How much impact can it create?

One pattern that immediately emerged was that child trafficking is a central issue that affects all age groups and genders. And while it may be difficult to address for older children, as they fall prey to trafficking due to complex socio-economic factors, there is significant room for improvement for younger children, who become victims mainly due to the lack of safe spaces, lack of supervision, and unawareness of safety dangers. This helped me narrow my focus to addressing child trafficking for young children of ages 7-10.

Assumptions & Hypothesis

After briefly exploring different directions, it was time to formally identify the unknowns. I considered them assumptions, so I can later create a hypothesis to verify them. I mapped them on two axes: high versus low risk and known versus unknown.

HYPOTHESIS

Based on the “high risk, unknown” assumptions, I decided to test the hypothesis that if we incentivize children to stay at CFS for more hours, it will increase their safety. We would know that this is true if the number of exploitation incidences reduces after implementing the solution.

Testing the Hypothesis

As I began thinking about testing my hypothesis, I realized that it was more difficult in my project than in most: it was nearly impossible to devise a prototype, have it quickly tested by my target users (Rohingya children in refugee camps), and check if my hypothesis is correct. For one, there were many logistical barriers. But more importantly, safety is hard to measure quantitatively, and even if we try to measure it, this would require observations over a long period of time.

Hence, given the time frame, I chose to reach out to more volunteers working in the Rohingya refugee camps, and validated my assumptions through one-on-one interviews.

And in one such interview, I had an “Aha!” moment. During our conversation, one of the volunteers (name omitted by request) insinuated that while children will be safe when they attend CFS, not all children can attend CFS regularly. Also, some children need to go out alone in the camp to get ration and water. What can we do about their safety? This made me rethink my approach to safety for this project and revealed the opportunity I was looking for.

Opportunity

How can we empower at-risk refugee children to be their own safety superheroes?

Stakeholder Needs

I began to further develop my idea by identifying all involved stakeholders and mapping their needs.

User Journey

Prototype

After exploring several different approaches, I arrived at the basic structure of my solution. MightyUs would be a workshop that teaches safety skills to children in the form of superpowers. Each skill would be explained in multiple ways — using hand gestures, games, songs, etc. A safety marshal would conduct the workshop with a small group of children.

My first prototype involved an “adventure walk”, during which the safety marshal would lead the children outdoors, and tell the story of a princess who is lost in the jungle and needs to return home safely. The children would think and advise the princess to use superpowers at each step of the way using what they have learned.

PROTOTYPE 1.0

The adventure walk was a good idea as it helped children be more comfortable in using the superpowers in the real environment. However, in my preliminary testing I observed that it was too long and did not leave enough time for explaining the superpowers to begin with. In the next iteration, I translated the adventure walk into an indoors experience that facilitated metacognitive learning through guided discussions.

PROTOTYPE 2.0

User Testing

Long before reaching the testing phase, I had begun investing efforts to be able to go to a Rohingya refugee camp in Bangladesh to test my prototype. Unfortunately, the intricate logistics of the process did not permit such a visit in the short time frame. Hence, I had to come up with a Plan B for testing.

I decided to have two detailed tests of my prototype, both with children of ages 7 to 10. I conducted the first with children in the US. In this test, my primary goal was to answer two question: Do my engagement strategies work with children of my target age group? And do children like the games I have designed to practice superpowers?

The second test was conducted with children in India by a safety marshal that I trained. Here, my goal was to observe how changing factors affect the implementation of MightyUs. Would children still be able to learn about the safety concepts if they have not been exposed to formal safety education in the school? What happens when MightyUs is conducted in a different language? Is anything lost in the translation? Do the examples and conversations still work? Is the guidebook self-sufficient for training the safety marshal?

These two tests helped me validate my key design decisions, and revealed fascinating insights.

USABILITY TESTING 1.0

USABILITY TESTING 2.0

Feedback

Is the workshop the right length?

When I first tested MightyUs, my time estimates were way off. What I thought would take an hour actually took 2 hours. I had also forgotten to incorporate breaks. In the next testing, I removed not-so-important phases of the workshop to make the experience more easy to digest, and added a break every 30 minutes. While it was wonderful to see children enjoying the workshop, 2 hours was a long time to keep up with all that energy!

Is introducing all five superpowers overwhelming?

I was skeptical at first. But surprisingly, the sequence of learning each superpower — a hand gesture followed by a game followed by a conversation — proved to be extremely engaging. It created pockets of physical and mental activities, and the change maintained their attention throughout the workshop.

Are conversations boring for ages 7-10?

While children of ages 8 and younger were more interested in the games and the hand gestures, children closer to age 10 were quite invested in reflecting over their choices. They found the conversation part to be intellectually stimulating.

Is the experience consistent across different contexts?

When the second user test was conducted in a different country, in a different language, and in a different cultural context, the safety marshal needed to use new context-appropriate examples to explain the same concepts. This demonstrated the need for contextual translation of the safety marshal guidebook into different languages to ensure a consistent experience.

Final Presentation

I presented MightyUs to the public at STATE / CHANGE, the 2018 MFA Interaction Design Thesis Festival.

Reflection

What were the challenges and what did I learn?

Working on this project and navigating through the challenges it posed taught me a lot, both about design and about myself as a designer. Here are some of the important learnings that will stay with me forever.

- From the beginning, the project was emotionally challenging for me. Reading and listening to the stories about these children and their suffering affected me deeply. The main learning from this project was how to have empathatic but not vicarious emotions, that is, how to mentalize but not mirror your user’s emotions.[1]

- As I developed my project, I constantly asked myself: “What makes an activity interesting for a child?” The answer, I learned, is co-creation. Children find an activity most interesting when they get to make decisions, and therefore feel more invested and have a sense of ownership over the activity.[2]

- Knowing what to do is one thing, but being prepared to act in a situation is different. This is where practice helps, especially for children. For example, it is not enough for children to simply know how to use a math technique; they need to practice it in different problems to really grasp it. And I re-learned this as an adult during this project.

- One size does not fit all. Each child is unique, and has different needs and attention span. Through iterations, I learned the importance of explaining the same concept in many different ways, so each child can learn from the way that suits them the most.

- Finally, not being able to test my prototype in an actual Rohingya refugee camp was a big setback in the project. I constantly struggled to design ways to evaluate the effectiveness of the project. Eventually, I learned that even if the testing conditions aren’t perfect, you can always find some similarities and use them to test specific design decisions. For example, children from different backgrounds may have different notions of safety, but might react the same way if you present them a situation that they find unsafe.

What were the other directions I explored and how did they lead me to design MightyUs?

At the outset of the project I didn’t have a specific goal. All I knew was that almost 60% of Rohingya refugees were children, many were orphans or separated from their parents, and amid all the chaos, they were suffering.

After narrowing down my focus to safety and well-being, my initial explorations were more at systems level, and viewed the problem through an architectural lens. I explored the possibilities of building a resilient community by creating safer environments for children and improving wayfinding using color-coded tents. However, the bylaws and difficult logistics turned out to be the biggest roadblock.

Learning from this, my focus further narrowed down to improving the existing learning centers at the camps, which already provide a safe environment for children but deal with the problem of a low retention rate. I explored different ways of incentivizing children to stay engaged at the learning centers. The key insight from this exploration was that “safety is the way of thinking”, which made me realize: if we don’t empower children to look out for themselves, they will still be at risk whenever they go out in the camp. This was my “aha moment” that led me to design MightyUs.

You can read more about these explorations here.